Last week, I attended talks for the Society of Anthropology of Paris meeting here in Montpellier. This has been an interesting experience for many reasons. For one, the talks have shown some interesting differences in the politics of anthropology in France compared to the United States.

The society was founded by Paul Broca in May, 1859, six months before Darwin published the Origin of Species. Broca discovered the language-associated area of the brain that bears his name, and was the one of the first to study the Cro-Magnon fossils, discovered in France in 1868.

While the society carries the general name of Anthropology, it now focuses on Biological Anthropology. The talks were mainly what in America we would call archaeology: analysis of bones and food residues from historic and prehistoric graves and occupation sites. Interesting stuff, but a bit narrow in scope. Few talks focused on human behavior, apart from a session of evolutionary psychology talks Thursday morning. In contrast to the American Physical Anthropology meetings, there were no talks on nonhuman primates. Most strikingly, there was no sociocultural anthropology at all; they have different meetings. Apparently, the divide between quantitative, evolutionary anthropology and qualitative, interpretive anthropology is even more stark in France than in the US. It seems more like an old, nearly-forgotten divorce than the uncomfortable marriage-on-the-verge-of-separation that still exists in American anthropology.

Another interesting aspect of the meetings was the use of language. The audience was mainly French, so I expected all the talks and slides to be in French. One speaker, based in England but not a native English speaker, gave her talk in English, but most of the language on her slides was French. The other speakers spoke in French, but for many of the talks, some or even all of the slides were in English. They frequently used English for technical terms, or when citing the title or findings from papers published in English. This was all very typical of what I have been seeing in departmental seminars at the University of Montpellier. The audience is mainly French, and most of the talks are in French, but visiting speakers usually give their talks in English, which everyone in the audience seems to understand reasonably well. And even when the speakers are French, their slides are sometimes entirely in English.

Before coming here, I had the impression that the French were highly protective of their language. They have laws requiring the use of French in commercial communications. They have L’Académie française, which tries to keep the language contaminated from foreign words like “le sandwich” and “les airbags.” Government agencies strive to come up with replacements for English words like “buzz,” “chat,” and “newsletter.” And in a recent study, France ranked right at the bottom of the heap of European countries for English language proficiency. And there’s a stereotype that the French are hostile towards people who can’t speak French properly (meaning most of us Americans).

In contrast to what I expected, though, most of the people I’ve encountered seem to have a very positive attitude towards English. People who know some English are eager to practice it. It’s not like northern Europe, where almost everyone in the cities seems to speak perfect English, but enough people speak English that in many situations, I have to make an effort to keep using French. The books in the lab library are mainly in English. My French colleagues read and publish their papers in English-language journals. Lab meetings and social interactions are mainly in French, but everyone can switch to English when needed (like when I give up in my struggle to explain something in French, which often happens). Outside of academia, English words and phrases occur in ads and on signs, and English-language songs dominate the radio (which is required by law to have 40% of songs in French during prime hours).

On a global scale, French has fallen dramatically from its 19th Century peak as a major language of empire, diplomacy, learning and culture. The percentage of American and British students studying French as a foreign language has dropped dramatically in recent decades. In much of North America, place names from Indiana (La Fontaine) to Minnesota (the redundantly named Mille Lacs Lake) reflect a long-lost empire, where French has been reduced to a declining minority language in Louisiana and even in Canada, where the proportion of native French speakers has dropped to 22% of the population. Even in Africa, where France had a vast colonial empire, French may be losing ground compared to other languages. In formerly French North Africa, Arabic competes with French for status as the primary language. South of the Sahara, French is still widely used as an official language, but Rwanda dropped French in favor of English, both in protest to French actions during the Rwandan genocide, and as part of an effort to build closer ties to the Anglophone East African Community. English is an official language of Africa’s most populous country (Nigeria) and the biggest economy (South Africa), and is the language of higher education in Africa’s second most populous country, Ethiopia, even though Ethiopia was never part of the British Empire. In Asia, English is widely spoken in South and Southeast Asia, including the second most populous country on the planet, India, whereas French has a small and declining number of speakers in former French Indochina.

In the thousand year-old rivalry between English and French, English seems to be gaining the upper hand.

Which has me wondering: what makes a language expand or contract? Does it mainly have to do with features outside the language, such as politics, demography, military conquest, and migration? Or does it also depend, at least to some extent, on features of the language itself?

I remember a night more than twenty years ago, during my first field season in Africa, studying baboons in Kenya. Gathered around the dinner table with American and Kenyan researchers, eating by the warm glow of kerosene lanterns, conversation turned to why English was so widely spoken. One of my American colleagues suggested that it was because English was so open to new words and ideas. Instead of trying to keep out foreign words, English readily adopts new words, like America adopts new immigrants.

I thought this was a funny thing to be saying in Kenya, where English was widely spoken not because the language is so open and friendly, but because it was the language of the British Empire, which colonized Kenya and much of the rest of Africa, as well as most of North America. The reason Kenyans and Americans had English as a common language had more to do with British seafaring, commerce, and military might than with any particular virtues of the language they spoke.

Similarly, all sorts of languages that might be hard for non-native speakers to learn have spread widely due to non-linguistic factors, such as the military might and demographic growth of their speakers. English speakers generally consider Russian, Chinese, and Arabic all hard to learn, but that didn’t stop these languages from spreading widely as their respective empires expanded.

All the same, thinking more about language from a Darwinian perspective makes me wonder whether, in the competition among languages, languages might change in ways that affect their relative competitive ability.

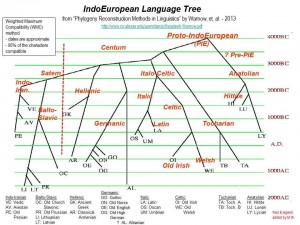

A language, like a biological species, has a life cycle, and is in competition with other languages. A language may spread widely and diversify, leaving numerous descendant languages, as Latin gave rise to the Romance languages, or Sanskrit to many modern Indian languages. Or it may shrink and die.

Growth or decline for languages occurs much the same way as it does for species: through births, deaths, and migration. Each time a child is born and learns her mother tongue, a new speaker is added to the language. If a language is no longer being transmitted to the young, but is only spoken by old people, the language will die with the last aging speakers.

Languages also migrate with their speakers. One reason English is spoken so widely is because seafaring English speakers established colonies around the world. In some of these colonies, English speakers became numerous and eventually swamped not only the native populations but also all subsequent immigrants. Some linguists call America a “language graveyard” because speakers of so many different languages come to America, only to have their children learn English and forget their mother tongue.

The total population of French speakers appears to be growing. In evolution, though, what really matters is relative growth rate. Genetic fitness, for example, is essentially a measure of relative growth rate of particular variants of genes (“alleles”) in a population. Alleles that have a high relative growth rate become increasingly common in the population, and may eventually reach fixation, present in essentially all members of the population. An allele, or a language, can become less common in the population if it is increasing at a slower rate than the population as a whole.

But unlike genes, language isn’t transmitted only from parents to offspring. Language can also be transmitted to completely unrelated people. In this way, a particular language is more like an infection.

As William S. Burroughs wrote and Laurie Anderson sang, “language is a virus from outer space.”

This is a thought-provoking image. Like a virus, a particular language is not part of the host’s own genome, but it uses the host to spread itself. However, it is wrong on two counts.

First, even though human language is an extremely peculiar and probably unique form of communication among earth species, invoking space aliens as an explanation is sort of the reverse of Occam’s razor: “among competing hypotheses, the hypothesis with the fewest assumptions should be selected.”

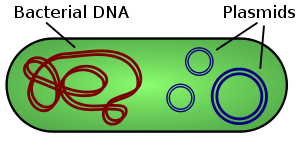

Second, even though language has some virus-like properties (it is can be transmitted from one person to another), it is really more like a plasmid than a virus.

Viruses are parasites that hijack the cellular machinery of other organisms to make more copies of themselves. But they usually don’t do anything to help the host, and in fact they often harm the host. A cold virus has been making the rounds of my family, and it has done nothing good for any of us. Instead, it lurks in our cells, churning out more copies of itself, and manipulates our bodies to ooze those copies out into the world to be spread to other people through coughing, sneezing, and running noses.

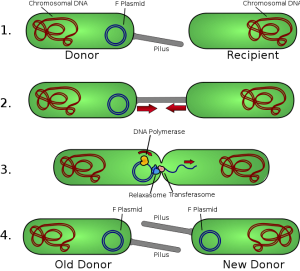

In contrast, at least as far as transmission is concerned, a language is more like a plasmid than a virus. Plasmids are little circular bits of DNA found in the cells of bacteria and other organisms.

Plasmids encode genes that provide handy tricks for the host, such as resistance to an antibiotic, or the ability to make a toxin. Plasmids can enable their hosts to live in what would otherwise be a hostile environment. Plasmids are useful to the host, rather than harmful, probably because of their mode of transmission: they can only be transmitted when the host reproduces (by dividing, in the case of bacteria) or when the host connects to another cell specifically to obtain new genes.

Like a plasmid, a language can do all sorts of useful things for its host. So much so that I’ve been making considerable effort to infect myself with a new one (French). The infection is far from complete (and is progressing rather more slowly than I might have hoped), but it’s far enough along that I can do a number of useful things with it, like order coffee and chocolate croissants, or renew my commuter rail pass, or get a new inner tube for the wheel of my jogging stroller, all of which would be harder to do using only the infection that I inherited (English).

The idea of language as a virus, or plasmid, or other transmissible agent is closely related to the term “meme,” which Richard Dawkins coined in The Selfish Gene, to make an analogy between cultural and biological evolution. The word has caught on, happily, to refer to Internet pictures of LOLcats and such, which are memes in exactly the sense that Dawkins originally meant: little bits of information that are able to get themselves propagated, and which undergo mutations and evolve overtime in branching lineages, just as genes do. In this sense, a language is basically a big complex of memes.

In this view, the individual words in a language are memes. Like genes, they evolve, becoming more or less frequent in a population over time, and undergoing mutations, and sometimes becoming extinct. Words compete with other words in the meme-pool.

The word computer, for example, is a Latinate word that came into English from French around 1646. At that time, the word “computer” referred to a person, not a machine: someone whose job it was to do calculations. Three hundred years later, when electronic calculating machines were invented, English speakers described the machines as “computers.” This sense of the word spread from English into a number of other languages, like Russian (kompyuter) and Swahili (kompyuta). But in France, the original home of the term “computer,” they instead use “ordinateur,” a word created in 1955 at the bequest of IBM France, because the term “computer” seemed “too restrictive in regard to the possibilities of these machines.”

So while languages have memes like viruses have genes, and like viruses they can be transmitted from one person to another, languages are usually useful to their host, rather than harmful. Why is that the case?

One reason might be the mode of transmission. A virus that is transmitted via saliva and snot is mainly interested in making its host produce lots of saliva and snot, and sneezing and smearing those fluids as widely as possible. The virus doesn’t share any genes in common with the host, and its reproductive success doesn’t depend on the reproductive success of the host. (Except for sexually transmitted viruses; though here, the interests of the host and virus still diverge, since the host doesn’t necessarily reproduce each time it has sex. A sexually transmitted virus benefits if the host lives long enough to keep having sex with more partners, but its own success doesn’t depend on whether the host actually reproduces successfully.)

In contrast, the surest means of language transmission is through the reproduction of the speaker. Languages take a long time to acquire (as I am painfully aware), and even though people say little kids learn languages quickly, it still takes years from them to learn their mother tongue properly, and from what I’ve seen in my own family, acquiring a new language is no trivial matter even when young. Because transmitting language from parent to child depends on successful raising of the child, the interests of the language closely coincide with the interests of the host.

But unlike a host’s own genome, a language can be transmitted horizontally as well as vertically: from host to host, rather than just host to offspring. It is in this respect that a language is more like a plasmid than either a virus. Like a plasmid, a language is useful to its host, it is transmitted to the host’s offspring, and it can also be transmitted to other unrelated hosts.

Of course, languages aren’t exactly like plasmids. It’s just an analogy, and any analogy can be pushed too far. But to me it seems a helpful analogy for thinking about the relative growth rates of different languages.

In an environment full of a particular antibiotic, such as penicillin, bacteria that acquire the penicillin-resistance plasmid will survive and reproduce, whereas bacteria without that plasmid will die out.

Likewise, in a world where English provides access to information, jobs, and money, people will have a strong incentive to acquire English.

On balance, I would guess that most of the reasons for the success of English have little to do with any particular properties of English. English is not, of course, intrinsically a “better” language than French, or Swahili, or Basque, or any other language. All of these languages can be used to communicate any idea. Most of the current advantages of English have to do with the social and political environment, which depends more on the happenstance of the British Empire spreading English across the world and planting colonies in fertile places, and the resulting the wealth and power of the United States and its impacts on global commerce, popular culture, science and technology. Currently a huge factor must be frequency dependent selection. As English becomes more widely spoken, it becomes increasingly advantageous to know it. This produces a snowball effect, benefiting English at the expense of other languages.

Still, are there some linguistic features that have helped English become widespread? Has English itself evolved in ways that make it more contagious? Perhaps the early history of contact with other languages, like Brythonic, Old Norse, and Norman French, helped to eliminate some features that were harder for non-native speakers to learn (most aspects of gender and case, for example). Elimination of tricky features seems to have happened with other languages. Swahili, for example, emerged as a trading language between Africans speaking Bantu languages and traders from Arabia, Persia and elsewhere. Many Bantu languages related to Swahili have tones, but Swahili doesn’t, perhaps as a result of interaction with Arabic and other languages.

Perhaps the combination of Germanic grammar and Romance vocabulary helps to make English easier for speakers of these two major branches of European languages to learn.

And also, given that much of the innovation in science, technology, and other ideas happens in Anglophone countries, and is communicated in Anglophone channels, English is rich in vocabulary useful for talking about these new things and ideas.

But another way that English might help propagate itself is through the production of little bits of language that are highly infections in their own right: songs, books, movies, and the like.

Popular music, and music videos, seem especially virus-like. A pop song doesn’t provide obvious benefits to the listener. Instead, it exploits the listener’s sensory biases in ways that make the listener want to repeat the experience.

Take the music video for Gangnam Style, for example. I watched it many times. I haven’t learned anything useful from it, except perhaps an explanation for why all the kids at the disco are dancing like they are riding ponies. This mainly Korean language video went viral, in part due to its catchy little hook of weird English.

In the book Plagues and Peoples, historian William H. McNeil argued that a key factor in history was the diseases carried by different peoples. The Eurasian landmass provided a massive Darwinian breeding ground for particularly nasty infectious agents, passed from domestic animals to people, and transmitted over thousands of miles of steppe by mobile horsemen. When Europeans first traveled to the Americas, they carried these highly infectious agents with them, with disastrous results for the Native Americans.

In a similar way, the vast Anglophone world serves as a global breeding ground for particularly infectious memes. I’ve talked with people who say they learned their English from listening to rap, or watching TV.

Perhaps official efforts to protect French actually serve to weaken the language, reducing its ability to resist infection, and reducing pressure on the producers of songs, books, movies and other cultural artifacts to be maximally infectious.