On my last trip to Ethiopia, I visited Guassa, at the top of the Great Rift Valley escarpment. In early August I traveled to Filoha, down towards the bottom of the Great Rift Valley, to visit my graduate student Kristy, who spent the summer working as a volunteer for Larissa Swedell’s hamadryas baboon project.

On the flight from Minnesota to Toronto I sat next to a woman in a black burqa that covered everything but her eyes, hands and feet. Dark henna designs decorated her hands. She spoke in surprisingly Minnesotan English. The number of people who both looked and sounded different from stereotypical Minnesotans increased as I approached the boarding gate for the connecting flight to Toronto. Connecting passengers had to stand in line to get stickers on our boarding passes to board the flight to Addis Ababa (which they spelled differently in Canada: Addis Abeba, and the announcer pronounced differently: “Ad-dees” instead of “Add-iss”). Most of the people in line were Ethiopians, and seemed a generally prosperous group: well fed, many of them tall and confident-looking, with fancy clothes, hair and jewelry. The line was chaotic, long, slow and crowded and midway through I gave up on it and tried to board. No luck; without the sticker I was sent back. So I was one of the last people to board the plane, and had to put my carry-on bag several rows ahead of my seat.

Ethiopia looks, smells, and sounds so different from other places I’ve worked in Africa. The people are diverse, with something like 80 different languages spoken in the country. But in general they look intermediate between sub-Saharan Africans and people of the Middle East. Which makes sense, because Ethiopia is right in between Africa and the Middle East. The national language, Amharic, is closely related to Arabic and Hebrew. Other common languages, like Oromo, are closer to Somali.

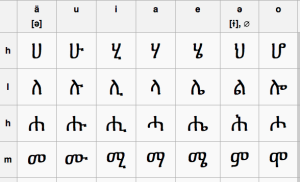

On the flight I worked my way through a bit of the Amharic phrasebook I got for my last visit to Ethiopia. The Amharic language uses a writing system that descends from an ancestor of Phoenician, the first alphabet and ancestor of Hebrew, Arabic, Etruscan, Greek and Roman alphabets. It is a syllabary, with 33 sets of symbols, each of which has 7 versions for the vowels eu (pronounced like in French, neuf), u, i, a, e, ə, and o. This means there are 231 symbols to memorize. Fortunately the symbols in a set change in a sort of regular way depending on which vowel they represent.

The series for m starts of looking like a pair of spectacles, for meu. For mu, there is a handle on the right side. For mi, there is a long handle on the right side, with a rightward line at the base of the handle, like an old fashioned pair of handheld spectacles. For ma, the rightward line disappears and you just get spectacles with a simple handle. For me, a little circle gets added to the handle. For mə, the handle shifts over to the left side and gets bent. For mo the handle stays on the left side but straightens up.

The Amharic script is beautiful, and having it on everything from road signs to Coke bottles imparts a distinctive feel to the country. We’re not in Kansas anymore.

The distinctiveness of the script stands as a reminder for how rapidly cultural evolution occurs. In general, the symbols look nothing like their distant cousins in other living alphabets. (There are some superficial similarities with the Georgian alphabet, from another remote mountain kingdom, but these are the result of accidental convergence, rather than cultural transmission.) The series for t does look rather like a Roman t, and the series for s looks like a Hebrew sh, but I don’t know if these are shared ancestral features or later convergences.

The variety of Afro-Asiatic languages spoken in Ethiopia suggests that this is an ancient center of diversification for this language family. Given the striking differences in appearance between speakers of Amharic and the peoples across the Red Sea in Arabia, this makes me wonder how much of the phenotypic difference in peoples has evolved in parallel with the language differences. As the proto-Afro-Asiatic people spread from their ancestral homeland, whether this was in Africa or Asia, surely they intermarried with local people along the way, so there would be gene flow as well as within-lineage change in phenotype.

There is a similar variety of appearance in speakers of Indo-European languages, from the pale blondes of Sweden to the brown-skinned, black-haired speakers of various languages of India. We tend to think of cultural evolution as being rapid and biological evolution as slow. But subtle changes, such as pigmentation of hair and skin, can happen fast enough that people who speak languages that are clearly part of the same linguistic family may have evolved look rather different.

People used to assume that language transmission was commonly horizontal, and that people speaking related languages aren’t necessarily genetic relatives. And it is true that anyone can learn any language, and imperial and commercial languages commonly spread across widely divergent social groups. But as Cavalli-Sforza and colleagues have shown, there is often striking convergence between the languages people speak and their genetic similarity. Particularly before the advent of modern transportation and mass migrations, people tended to stay close to home, marry people from nearby and within their own language group. As a result, speakers of related languages are commonly genetically related as well (at least for languages with a long local history, as opposed to recently adopted commercial or imperial languages).

Amharic has a whole set of glottalic consonants, produced with glottal stops (like the “t” sound in “butter” with a Cockney accent). This, combined with a vocabulary that is mostly unrelated to European languages or Swahili, gives it an extremely foreign sound to me. But there are some similarities. Swahili has lots of loan words from Arabic, and many of these words are also similar in Amharic, such as words for higher numbers (thirty, forty, and fifty are thelathini, arobaini, and hamsini in Swahili, and seulassa, arba, and hamsa in Amharic). Because of the Italian occupation of Ethiopia (193x-194x), there are also lots of Italian loan words: bravo, ciao, and machina (car).

Ethiopia smells different in part because of the distinctive spices in the food, especially berbere. On the long flight from Toronto to Addis Ababa, the cabin air smelled strongly of berbere. I had my hopes up for excellent meals of Ethiopian style food. Instead we got rubbery pasta and limp vegetables. The scent of berbere must have emerged just from the clothes and pores of so many spice eaters on the plane.

Historically, Ethiopia was a high mountain kingdom surrounded by deserts. This helped it maintain its independence and distinctiveness from surrounding countries and would-be invaders. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church has endured for some 1,500 years or more when most of the surrounding peoples converted to Islam. The distinctive round Ethiopian churches help make this country seem so different from, say, Tanzania, where both Islam and Christianity are more recent arrivals. (The coast of Tanzania has long been Islamic but its history in the interior is more recent.)

Stepping off the plane in Ethiopia from the humid warmth of Minnesota was a shock. Addis is high in the mountains and cool. I felt rather cold in my sandals and short sleeves.

The whole arrivals and customs area has been renovated since my visit three years ago, thanks to Chinese money for an entire airport renovation. Immigration was slow and chaotic, but generally hassle-free. People standing at the entrance area checked passports for visas and sent you to the line if you needed to get a visa. The visa line required several steps: first you get the visa, which they fill out by hand in Amharic, then you stand in another line to pay for the visa ($50 now, up from $20 three years ago), and then you stand in another line where they check that you have the visa and paid for it. I found myself standing in line next to the woman in the black burqa who had been on the flight from Minneapolis. She seemed just as confused by everything as I was.

I got $100 worth of Ethiopian birr from an ATM in the baggage claim area. The machine spit out a brick of crisp new bills, more than 2100 birr in 100s, 50s, 10s, 5s and 1s. I couldn’t fold my wallet with all those birr so put them in my travel pouch.

Outside the baggage claim stood a crowd of people welcoming the new arrivals, including family, friends, and hotel and tourist staff. Someone asked me if I was from Egypt. Ethiopia is one of the few places where I’ve mistaken for a Middle Easterner. Later someone asked if I was from Saudi Arabia.

Outside in the parking area I soon found my driver. He introduced himself as Ermias, “which is Jeremiah in the Bible in our language.” I recognized the car as the same one I took to Guassa three years ago. Only then did I remember that this car had broken down for about an hour on the road to Guassa. When I got into the car and rolled down the window, the round, spinning end of the handle came off in my hand.

We drove down the broken, potholed streets of Addis to the house of the tour operator, so I could pay for the trip to Filoha. Outside the gates, sheep foraged in the grass.

It was Sunday morning, many people were in church and few cars were on the street. The rough streets ensured that the going was slow even without much traffic. But there were signs of new construction everywhere. Many new buildings enclosed in flimsy looking wooden scaffolding.

When Ermias stopped to change money, I bought a liter of cold water to drink along the way. We stopped for gas at what seemed to be a BP station (green signs, but in Amharic letters). The station was off to the side of the road and downhill a bit, with loose gravel and dirt covering the connection to the road. It seemed as if someone had dropped the gas station here by accident. Huge trucks competed for space in the queue with tiny cars. Payment seemed entirely cash and directly to the attendant at each pump.

Last time we drove up, up, up to Guassa, up to the crest of the rift escarpment. This time we drove down, down, down to Filoha, down towards the bottom of the rift. According to my GPS, one gas station in Addis Ababa is at 2,219 m (7,323 feet), Darjeeling Cliff at Guassa is 3,383 m (11,164 feet), and Filoha is 728 m (2,402 feet) above sea level. Filoha is thus similar in elevation to Gombe, which my GPS says is 774 m (2,554 feet) at the mouth of Rutanga Stream. The rift valley goes lower, eventually dropping well below sea level in the Danakil Depression, where the Awash River flows into a dry dusty pan and disappears.

We took the new expressway (built by the Chinese), which ran parallel to the new railroad (also Chinese built), which both link Addis to Djibouti, the closest seaport (now that Eritrea has become independent, depriving Ethiopia of a direct connection to the coast). The expressway is a dual carriageway toll road with six lanes of traffic, which contributed to the feeling of not being in Africa at all.

Close to Addis the countryside is well watered with expansive fields of green. Further down into the rift we saw more signs of geological activity: vast fields of black lava rock interspersed with green grass and isolated trees. The further down we went the more marabou storks and vultures appeared by the side of the road.

I tried to stay awake to enjoy the whole ride but was too sleep deprived and drifted in and out of consciousness. We left the freeway to a join a road that was narrow but still freshly paved and smooth. More Chinese roadwork, I’m sure.

The Chinese are playing a role in Ethiopia – and much of the rest of Africa – similar to what the British played throughout much of the world in the 19th Century, and the Americans in the 20th Century. I suppose the British nowadays are too busy with finance, and the Americans are too busy developing new apps for the iPhone, to bother with such concrete things as roads, buildings and railways in Africa.

We passed a truckload of camels, packed together sitting down with their necks upright. Ermias said they were going to Saudi Arabia.

We stopped for lunch at Metehara, the last major town before Filoha. We parked in front of a small restaurant. On a raised area at the front of the restaurant, a woman knelt before a set of coffee cups, preparing coffee in the bunna ceremony. A charcoal burner held three sticks of burning incense. Ermias explained that they only had fasting food, meaning vegetarian items, because of the religious holiday.

We stopped for lunch at Metehara, the last major town before Filoha. We parked in front of a small restaurant. On a raised area at the front of the restaurant, a woman knelt before a set of coffee cups, preparing coffee in the bunna ceremony. A charcoal burner held three sticks of burning incense. Ermias explained that they only had fasting food, meaning vegetarian items, because of the religious holiday.

“Which holiday is it?”

“Something from the Bible.”

Ermias ordered something for me that turned out to be a huge round platter with a huge round flat piece of spongy enjera bread with little piles of tasty vegetarian delights. After lunch Ermias changed the flat rear tire of his car. His skin glistened with sweat after just a few minutes work. It was getting hot down here.

We soon reached the park gate of Amhara National Park. This is the major national park in southern Ethiopia. We drove off the paved road to the little building by the simple gate, where a sign explained the rules and fees.

Most of the tourist facilities are to the south, along the Awash River, but we would be going to the very northern end of the park, 32 km away. I paid my park entrance fee, plus an additional 150 birr ($7) for an armed guard to accompany us to Filoha. The risk of banditry makes armed guards a necessary requirement for travelers in the park.

We drove back across the paved highway onto the gravel road leading north. The gravel road suddenly jogged sharply to the right, to make its way around the new Chinese-built railroad that cut directly across the park. This must be a huge barrier to wildlife in the park now, as the tracks travel between deep drainage ditches dug on either side.

We drove slowly down the hot, dusty, winding gravel and dirt road. A low thicket of Acacia trees extended in all directions from either side of the road, with some distant hills and mountains visible. From time to time, birds flew out in brilliant flashes of color. These were birds familiar to me from when I habituated baboons in Kenya, and from visits to other dry parts of East Africa: White Headed Buffalo Weavers, Bee Eaters, Malachite Kingfishers, Lilac Breasted Rollers, glossy Longtailed Starlings. In America, Starlings are kind of dull, mottled brownish black nuisance birds. In Africa, Starlings are glorious birds with iridescent plumage and brilliant colors. I felt an intense sense of homecoming seeing the familiar birds and trees of the Acacia woodland. From time to time a dik-dik, a tiny little fairy of an antelope, bounded away in the bushes. A lesser kudu crossed the road, a beautiful striped antelope with long spiral horns.

On the highway, the wind roaring past the open windows kept us cool. On the slow gravel road, the sun baked the slow moving car, and the air provided no relief. I kept thinking that we were pretty remote now, we were about to get to camp, but then we would keep driving for ages more. A set of rounded white structures showed in the distance, looking like a set of tents. That must be camp! But as we got closer, it became clear that these were simple huts of sticks covered in tattered white sheeting.

“An Afar camp,” Ermias explained. “Pastoralist people.”

Soon after we passed a group of Afar herders on the road: people with very dark skin, wearing bright white cloths draped over the shoulder and wrapped around the waist. The Afar people are the namesakes of the taxonomic name of Lucy, the famous fossil found not too far from here: Australopithecus afarensis. They herd cattle, goats and camels. They speak a Cushitic language related to Somali. Technically they are not supposed to be in the National Park but thousands of them live in Awash and keep their herds here.

The road went on and on and on. The heat grew increasingly oven-like. The landscape grew monotonous and in my sleep-deprived state I faded in and out of awareness. The water in my bottle became as hot as tea.

We passed through blasted landscapes of lava rock, down steep gullies, and passed mysterious peaked mounds of rock (built by Italians during the war, and said to cover bombs). Then, after an hour or more of Acacia scrub, stands of Doum palms appeared along the side of the road, at the edges of wetlands that flooded the road itself. We drove through water and mud. A craggy wall of lava appeared to the left. To the right, the peaked roofs of huts appeared.

He parked the car by one of the huts in what appeared to be an empty, quiet camp.

“They know you are coming?” Eremias asked.

“Yes, they know I am coming.”

Soon two women appeared, smiling and walking down the hill towards us from another pair of huts: Alex, who is doing her dissertation research here, and Kristy, looking red from the sun and very much at home in Filoha.

I asked Ermias to take a picture of us.

“Okay, now we have evidence of my visit.”

“Right, so now you can leave?” joked Ermias.