Reading the news these days, one might get the impression that evolution is just for Democrats, not Republicans. For example, in a recent (23 August 2011) post for the Washington Post, Richard Dawkins calls Republican Governor of Texas a “fool” and an “ignoramus” for expressing some doubts about evolution, and implies that these labels apply to anyone voting Republican. The next day (24 August 2011), Ann Coulter published her own post, calling Richard Dawkins “retarded” and trotting out a series of tired old arguments against evolution.

Coulter is just plain wrong on evolution. At the same time, though, Dawkins is wrong to disparage the political opinions of people who happen to vote Republican.

Coulter is wrong about evolution in many ways. For example, she claims that if “Darwin were able to come back today and peer through a modern microscope to see the inner workings of a cell, he would instantly abandon his own theory.” Darwin, however, spent many years peering through microscopes at the inner workings of barnacles, and it was the fascinating complexity of their anatomy that deepened his understanding of evolution. Modern understanding of the inner workings of cells has further deepened scientific appreciation for how evolution works. The patterns of DNA encoded within each living cell have confirmed Darwin’s insight that every living thing on earth is part of one big family, the Tree of Life.

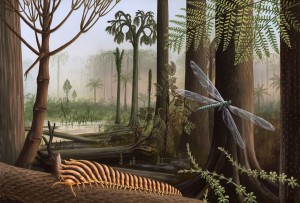

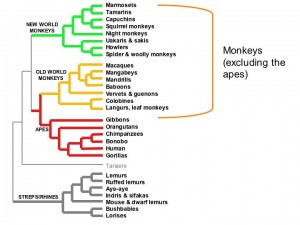

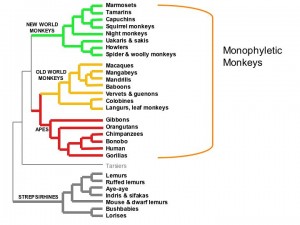

Comparing the similarity of DNA sequences has revealed some interesting surprises – for example, humans and chimpanzees are closer kin than chimpanzees and gorillas, even though gorillas look basically like giant chimpanzees – but has also generally confirmed the big picture of the tree that would be expected from shared descent with modification: humans and chimps are twigs on the primate branch, sprouting from the mammalian limb, emerging from the great trunk of vertebrate life, which near the roots of the tree joins with other great trunks and side branches: fungi, plants, and a variety of different bacteria.

Similarly, Coulter brings out the old argument from probability theory, that “it is a mathematical impossibility, for example, that all 30 to 40 parts of the cell’s flagellum – forget the 200 parts of the cilum! – could all arise at once by random mutation.” But as Dawkins clearly explains in The Blind Watchmaker – which Coulter doesn’t seem to have read, or at least not understood – evolution doesn’t throw together everything at once. Evolution works with small gradual changes, building on what exists already. It would indeed be statistically highly improbable to throw even a small number of things together at random and have them work together at all, much less well. But evolution doesn’t do that. Instead, evolution blindly, mindlessly tinkers with what already exists, changing a little bit here and there at random, and then lets these different variants fight it out in the arena of natural selection.

Coulter has made a career of strident political writing, and while the tone of her piece may be more appealing to those who already agree with her than persuasive to her opponents, it is at least consistent with her genre. Richard Dawkins, however, is a scientist. Indeed, he is one of our clearest thinkers and writers on evolution. It is disappointing that he here conflates views on evolution – which he rightly calls a scientific fact – with views on politics – which are, after all, opinions.

We have abundant evidence from fossils, geology, genetics, molecular biology, physiology, development, biogeography, and numerous other fields of study that evolution has occurred and continues to occur all around us. In contrast, while political opinions bear some relation to facts, they nevertheless pertain mainly to matters about which people with intelligence, experience and expertise continue to debate vigorously. Political questions are generally much more complicated and harder to be sure of than questions in the natural sciences, and they often relate to values – what people care about – rather than things that can be objectively determined to be true or false. Many political questions concern economics – which is routinely insulted as “the dismal science” because economists have such a great diversity of opinions. And why is economic opinion diverse? Is it because economists are more stupid or quarrelsome than other academics? Or is it because economies are just incredibly complex and difficult to understand?

Contrary to what readers of Coulter and Dawkins might be led to believe, evolution is not just for Democrats. The scientific truth of evolution doesn’t depend on a person’s political affiliation. People with all sorts of different political views have made important contributions to evolutionary theory. The great population geneticist J.B.S. Haldane was an idealistic Marxist and from 1937 to1950 a member of the Communist Party. Haldane’s colleague Ronald Fisher, described by Dawkins as “the greatest biologist since Darwin,” was politically conservative. Nobody today much cares about Haldane’s or Fisher’s political views. It’s their scientific ideas that have survived the test of time.

Darwin’s own political views might be hard to categorize today, because political views change greatly over time. Darwin shared Lincoln’s exact birthday (February 12, 1809) and Lincoln’s abhorrence of slavery. Maybe, if Darwin had been American, he would have voted Republican. I don’t know. But we don’t remember Darwin for the stances he took on the pressing political issues of his day. We remember him for his idea of evolution by natural selection, which remains just as powerful today as it was 150 years ago, and will continue to be so 150 years from now, or 150 thousand years from how, when the political issues we care so much about today will long be forgotten.

Indeed, evolution by natural selection will necessarily occur wherever life exists in the universe. If intelligent beings exist on a planet orbiting, say, Alpha Centauri, we can be sure of two things: (i) life on their planet undergoes evolution by natural selection and (ii) the question of whether to vote Republican or Democrat will be entirely, er, alien to them.