In college, I took a class taught by Amy Kass called “Human Being and Citizen.” We read and discussed selections from the Bible, Homer, Aristotle, Plato, Shakespeare, Kant, Rousseau, Dostoevsky, and others. After one class, frustrated and confused by the arguments presented in these widely varying texts, I approached Mrs. Kass and asked her,

“What is your foundation for morality?”

She looked at me with a wry smile and a glint in her eye, and said,

“Standing on one foot?”

I understood her point—the impossibility of responding adequately to such a question—but I didn’t get the reference she made until some years later, when I came across a story told in the Talmud (Shabbat 31a) in which a gentile seeking to be converted to Judaism approaches the famed Rabbi Hillel with the challenge,

“Convert me on condition that you teach me the entire Torah while I am standing on one foot.”

Rabbi Hillel responded, “What is hateful to you, do not to your neighbor: that is the whole Torah, while the rest is the commentary thereof; go and learn it.”

Rabbi Hillel lived in Jerusalem during the reign of King Herod, and is thought to have died when Jesus was still a child. Hillel’s version of the Golden Rule would thus belong to a tradition that already existed when, according to Luke, Jesus gave his own version of the Golden Rule in the Sermon on the Mount:

“Do unto others as you would have others do unto you” (Luke 6:31).

Jesus presents the Golden Rule with a positive spin: “do unto others” rather than “do not what is hateful.” Either way, this rule provides a compass for navigating social life, for living well with others. It is so familiar that it seems obvious, even trivial. But it is a radical rule, both in its simplicity, and in its departure from other views of how we should act in the world.

For example, in Plato’s Republic, written around 375 BCE, Thrasymachus proclaims:

“I say that the just is nothing other than the advantage of the stronger” (338c, p. 15).

In other words: “Might makes right.”

Another definition emerges in conversation with another character, Polemarchus:

“Justice is doing good to friends and harm to enemies” (332d, p. 8).

While Plato doesn’t endorse either of these views, none of the characters in his Republic propose anything quite like the Golden Rule as a guide to living. Even Plato’s hero, Socrates, comes to a rather modest conclusion: justice is “minding one’s own business” (433b, p. 111).

The Golden Rule may not be a perfect guide to every situation—after all, people’s preferences vary. That would be one reason that holy books contain commentary, not just a simple statement of one rule for living. But the rule provides a good starting point: taking the perspective of other people rather than just looking out for your own interests.

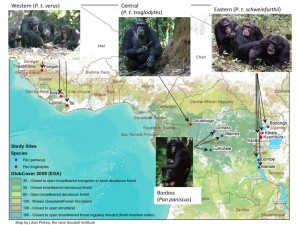

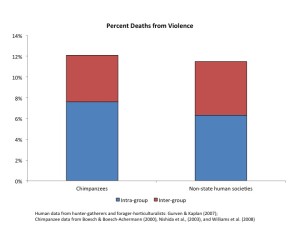

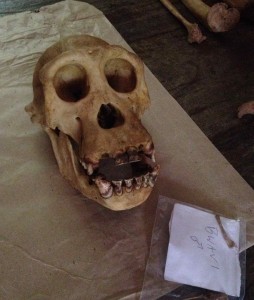

The chimpanzees that I study in Tanzania act as if they live according to those two views from Plato’s characters: “might makes right,” and “do good to friends and harm to enemies.” Chimpanzees live in a zero-sum world of intergroup relations. A win for my group is a loss for yours. Most of the stories in history books—invasions, conquests, the rise and fall of empires—follow similar zero-sum rules.

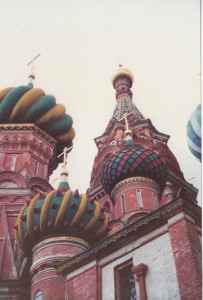

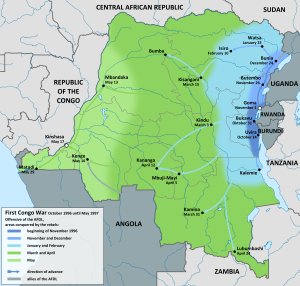

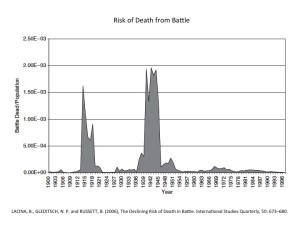

This week marks the one-year anniversary of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Since 24 February 2022, nearly every day has brought appalling new stories. Cruise missiles blasting civilian apartment buildings, schools, and hospitals. Massacres, torture, rape. The war seems anachronistic, a throwback to the tank battles of World War II and the trench warfare of World War I. In 1945, hoping to prevent World War III, the founders of the United Nations agreed to “live together in peace with one another as good neighbours,” vowing “that armed force shall not be used, save in the common interest.” The United Nations Charter signaled a profound shift away from the view that war is a legitimate tool of national interest, to something more like the Golden Rule.

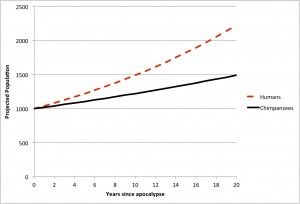

Unlike chimpanzees, we don’t have to fight our neighbors. Instead, we can engage in mutually beneficial exchanges. We help each other out. We can trade information. Where is that migrating herd of wildebeest heading? Where is a waterhole that is not dried up? We can exchange favors. You can come hunt on my land for a while, if you let me take water from your land. We can exchange goods, such as decorative pigments and shells, and material for making tools. The archaeological record in Africa indicates the people have engaged in such trade for hundreds of thousands of years, based on the finding of materials such as obsidian many kilometers their sources—much further than people are likely have traveled on their own.

As humans, we depend on help from others. In recent centuries, developments in economics and technology have multiplied exponentially the ways in which we depend on others around the globe. A major lesson from the modern world is that everyone gains from living as good neighbors, and everyone loses from war. My hope is that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will remind the world of the horrible costs of war, resulting in renewed efforts to build an international community based more on the Golden Rule than the law of tooth and claw.

Of course, while we can aim for an international community composed entirely of good neighbors, the world we live in contains bad neighbors, who must be dealt with. In the book of Luke, immediately before pronouncing the Golden Rule, Jesus proclaims:

“Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who mistreat you. If someone slaps you on one cheek, turn to them the other also. If someone takes your coat, do not withhold your shirt from them. Give to everyone who asks you, and if anyone takes what belongs to you, do not demand it back.”

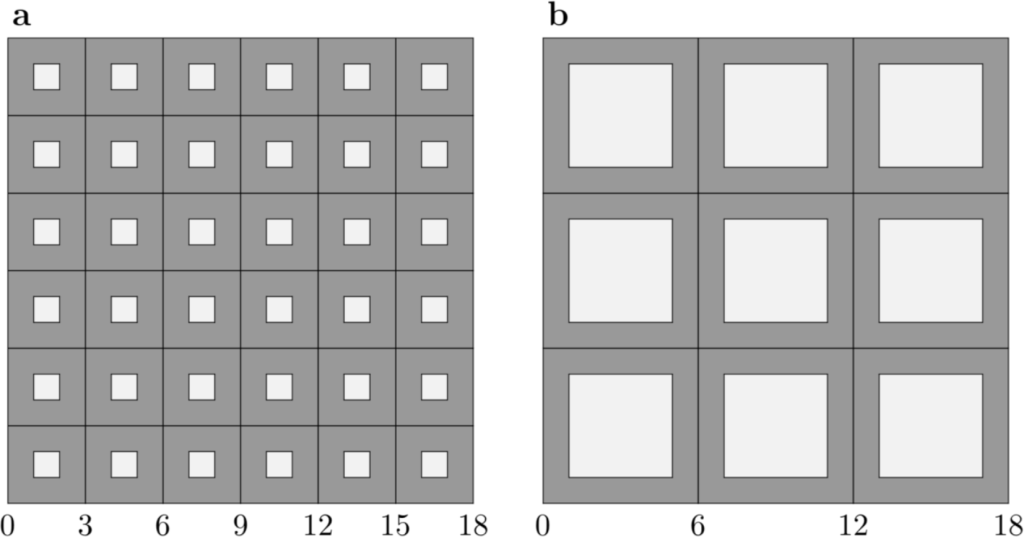

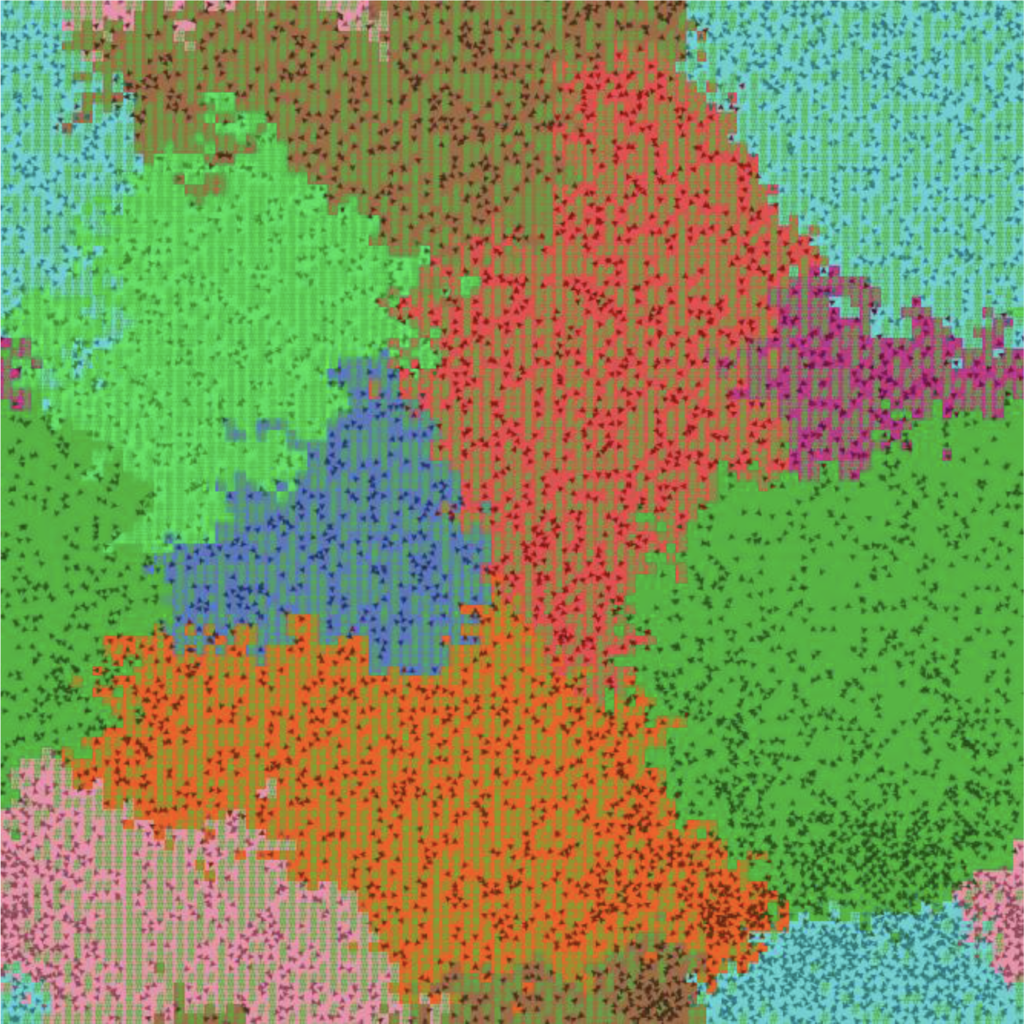

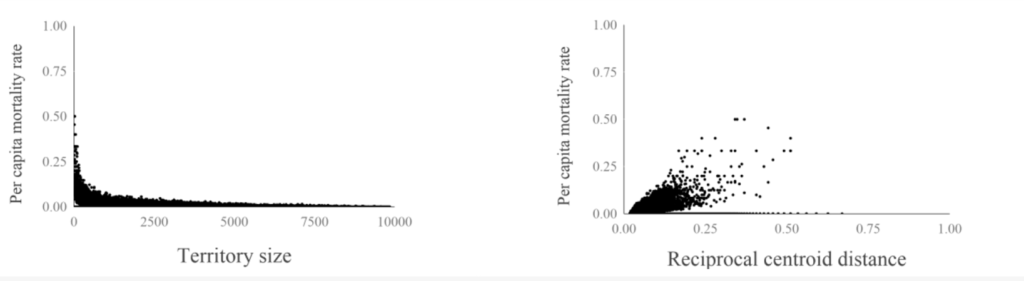

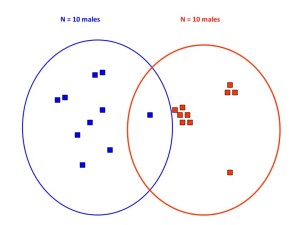

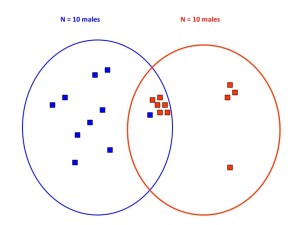

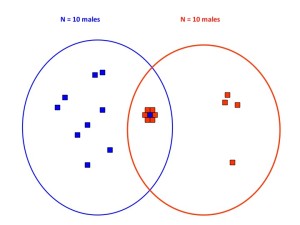

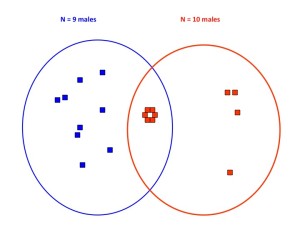

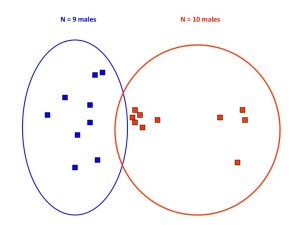

Perhaps George Price, who underwent a profound conversion to Christianity late in life, had this passage in mind when working on the Hawk-Dove game, which he published in a 1973 paper with John Maynard Smith. In this foundational work of evolutionary game theory, the authors modeled “turning the other cheek” with the strategy of Dove: when conflict arises, retreat from the aggressor. In a world composed entirely of Doves, everyone would benefit: nobody would fight, so nobody would suffer injuries. However, mathematical and computer modeling found that the world of Doves is vulnerable to invasion by Hawks: individuals that always fight to take what they want. Everyone is worse off in a world with Hawks, but Doves alone cannot prevent a Hawk invasion. Doves can, however, invade a world composed of entirely of Hawks, because Doves avoid the costs of constant fighting. Maynard Smith and Price concluded that the Evolutionarily Stable Strategy consists of a mix of Hawks and Doves—or of individuals using a mixture of both strategies.

In the long peace that followed World War Two, the peoples of Western Europe learned to live as Doves, enjoying the benefits of being good neighbors to one another, rather than seeking conquest and empire. The mostly peaceful collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 brought with it the hope that Russia too would become a Dove, and everyone would win. With the invasion of Ukraine, however, Russia revealed itself to be a Hawk. So long as Hawks exist, the Golden Rule alone will be an insufficient guide to international relations. To defend against Hawks, nations must instead follow the advice of Polemarchus: “Do good to friends and harm to enemies.” And if the logic of the Hawk-Dove game is sound, that there will always be Hawks.

(If you are interested in exploring the dynamics of the Hawk-Dove game, see this NetLogo version of the game developed by Kristy Crouse here. )

References

Babylonian Talmud: Tractate Shabbat, Folio 31a https://halakhah.com/shabbath/shabbath_31.html

Bloom, A. (1968). The Republic of Plato. Basic Books.

The Holy Bible, new international version. (2011). Biblica.

Smith, J. M., & Price, G. (1973). The Logic of Animal Conflict. Nature, 246(5427), 15-18.