Below is the text (more or less) from the TEDxUMN talk that I gave on 03 May 2015. A video of the talk is here.

I grew up in the Cold War.

The books, movies, and music were filled with fears of the end of the world.

One of my favorite albums was Pink Floyd’s The Final Cut: A Requiem for the Post-War Dream.

The album ended with the song: Two Suns in the Sunset.

The second sun being, of course, a thermonuclear explosion.

Looks like the human race is run.

War seemed inevitable. There was no way out.

But despite all the doom and gloom, it turned out these were actually the final years of the Cold War.

In 1989, the Berlin wall fell, and in 1991 the Soviet Union collapsed, not with a bang, but with a whimper.

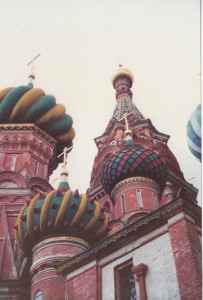

I was lucky enough to get a glimpse behind the Iron Curtain just as it was coming down.

I had a fellowship to study in England that came with money for summer travel in Europe.

I used that money to travel to Russia, then all the way to China on the Tran-Siberian Railroad. It turns out that this was the last summer that the Soviet Union existed.

And on the other side of Iron Curtain I found that people were pretty much just like us.

Walking around Moscow near Red Square, I saw Soviet soldiers – boys, really, about my age – playing around in a children’s park, taking pictures of each other.

This was an exciting time, with the Soviet Bloc and China opening up to the outside world.

It gave me hope that maybe war was something we can overcome.

I grew up worried about war but fascinated by apes.

As a kid, I saw Dian Fossey on TV with mountain gorillas and thought to myself: that’s what I want to be when I grow up.

It’s because of war, though, that I don’t study gorillas.

The mountain gorilla study is located in Rwanda, a tiny country in the heart of Africa. After college, when I wrote to the directors of the gorilla study asking if they needed research assistants, they wrote back saying they were closing camp down because Rwanda was descending into war.

The war continued for years, killing hundreds of thousands of people.

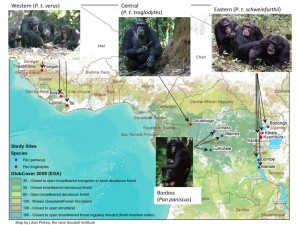

So instead of growing up to study gorillas, I study chimpanzees.

You can’t always get what you want.

But if you try sometimes,

You might find,

You get what you need.

And what I needed was chimpanzees.

I needed chimpanzees because they are our closest living cousins.

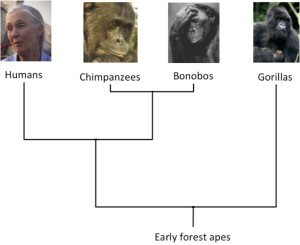

Chimps and gorillas look a lot alike: hairy, knuckle-walking apes. The the two kinds of chimpanzees — “common chimpanzees” and bonobos — are more closely related to us than they are to gorillas.

And chimpanzees share a number of unusual traits in common with people.

They make and use tools – like this one here, who is using a stick to fish termites from their nest so she can eat them:

Like humans, chimpanzees work in groups to hunter other animals.

And like humans, chimpanzees defend group territories, and sometimes gang up on members of other groups, attacking and killing their enemies.

It is this warlike behavior that I set out to study, looking for clues about how the origins and evolution of warfare in our own species.

So I went to study chimpanzees in Kibale Forest in western Uganda – much safer, I figured, than studying gorillas in war-torn Rwanda.

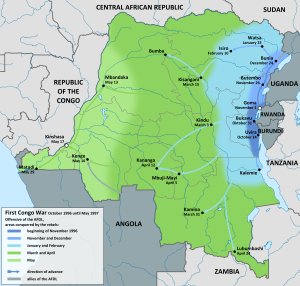

As it happened, though, the war in Rwanda spilled over into Congo, resulting in a huge war that eventually involved nine African nations and killed millions of people.

Kibale is just 30 miles from the border with Congo. On a clear day in Kibale you can see the snowcapped Ruwenzori Mountains that form that border.

And while the war raged in Congo, a Ugandan rebel group, the ADF, set up in those very mountains. Some of them were even rumored to be hiding in Kibale. The ADF bombed cafes and buses around Uganda, and attacked a school just 20 miles from us, burning 80 students alive.

At one point bandits attacked our village. They robbed and beat chimpanzee project field assistants, and shot and killed the brother of one of our employees.

And right around this time, one of the same field assistants who had been robbed found our chimpanzees beating on the freshly killed body of a male chimpanzee from another community.

The stranger’s body was covered in bites and other wounds, and his throat was torn out.

Why do chimpanzees do this?

Lots of other animals defend group territories, but in most species, they just chase their enemies away, rather than hunt them down and kill them. What’s going on?

Why do we kill?

One explanation for why we kill is the imbalance of power hypothesis, developed by Richard Wrangham and colleagues.

Behavioral ecologists think of aggression as the result of a cost-benefit calculation: animals use aggression as a strategy to get some benefit, when it looks like the benefit will be greater than the cost.

The benefits of aggression in chimpanzees are similar to those in other group territorial species: territory, food and mates.

But the costs of killing are low because of an unusual social structure that chimpanzees share with humans: fission fusion societies.

If we were gorillas, we would travel in a stable group all the time: a single male with his harem of females and kids.

But instead we live like chimpanzees: sometimes gathering in big groups, like we are now, and sometimes separating off into smaller groups.

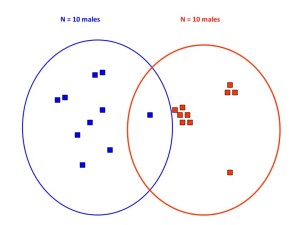

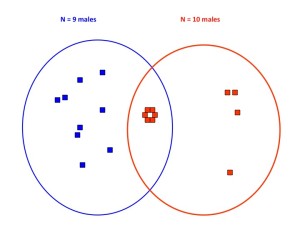

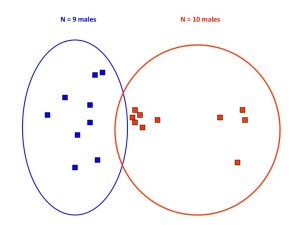

For example, here are two neighboring territories: Blue and Red.

Each territory has 10 males.

There’s not much food at the moment in the Blue territory, so the Blue males are traveling in small parties, mainly ones and twos.

But there’s more food in the Red territory. They can travel in bigger parties, including this one with six males.

These six males have safety in numbers, so they go on a border patrol.

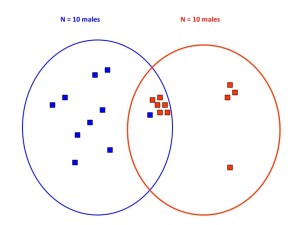

There they find a single blue male off by himself.

Bad luck for the blue male! The red males surround him, gang up on him, and kill him.

Now Blue only has 9 males.

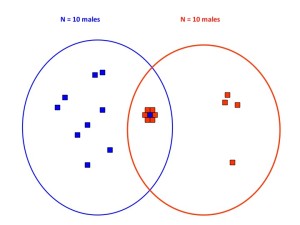

With fewer males, Blue loses territory to Red. The Red males get the benefit of a larger territory with more food for themselves, their mates and their offspring.

The imbalance of power hypothesis makes some clear predictions.

For example:

Males should visit borders only when in larger groups.

Parties with more males should be more likely to approach strangers, to win fights, and to kill their enemies.

And winners should gain more territory.

I’ve spent much of the past 20 years testing these predictions.

I used playback experiments to test how males would respond to a stranger.

In each experiment, I played back a single pant-hoot call from a foreign male.

A pant-hoot sounds like this:

(And this is what a professor imitating a pant-hooting chimpanzee looks like:)

Hearing a single stranger calling in the distance had a big effect on the chimpanzees.

In parties with just one or two males, they looked towards the speaker, which was hidden some 300 m away. Sometimes they just stayed still, looking, but in about half the cases they slowly, cautiously walked towards the speaker.

In parties with three or more males, the response was totally different. They gave a loud “wraa!” response right after hearing the call, dropped down from their trees, and rapidly walked single file towards the speaker.

After each playback, we quickly packed up the speaker and carried it away, while one of us stayed at the speaker location to see what happened. Often that person was me.

I remember sitting there quietly in the undergrowth when suddenly I heard footsteps. I saw a line of males walking single file, their hair out, looking for someone to kill.

They glanced my way, but they weren’t interested in me. They knew who I was. They were looking for a stranger.

More recently, I’ve analyzed data from all the long-term study sites for chimpanzees.

What I’ve found is that killing is widespread, and occurs at most study sites.

In cases of intergroup killing, the attackers had an average 8:1 advantage over the defenders.

Analysis of long-term data has found that groups with more males expand their territory and obtain more food for self, mates, and offspring.

Just like chimpanzees, people are sensitive to the costs and benefits of aggression, and they prefer low cost fights: unfair fights that they are likely to win.

In human warfare, numbers matter, but even more important is weapons. Whenever people have developed a military advantage they have used it to conquer.

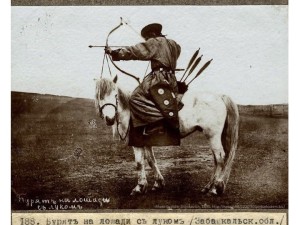

The Mongols, for example, swept across Eurasia with their fast horses and mounted archers.

But conquest, in humans and chimpanzees, is a zero sum game. Any benefit for my group is a loss for yours.

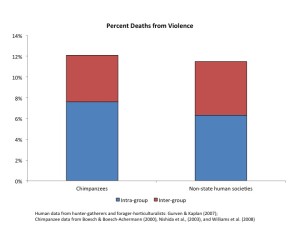

This is a risky game to play. About 12% of chimpanzees die from violence – that’s about out of eight.

The tables in this room seat about 8 people – so if were living in such a world, on average one person at each table would die from violence.

In human groups that live much like we did for most of our evolutionary history – as hunter gatherers and small scale tribal societies – the rate of death from violence is also about 12%.

For both chimpanzees and people, playing this zero sum game of group territorial behavior means a high risk of death by violence.

But unlike chimpanzees, people have found some ways out of the zero-sum trap and have learned to play positive-sum games.

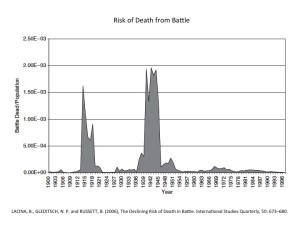

This slide shows the risk of dying in battle from war in the 20th Century, for people worldwide:

The two big spikes are the First and Second World Wars.

What’s really striking about this graph is that there haven’t been any more really big spikes since 1945.

Nuclear weapons have raised cost of war so much that there have been no great-power wars in 70 years

People have – so far—avoided the horrible costs of direct nuclear exchange.

People are also sensitive to the benefits of peace, and these have increased over time, as the world has gotten more interconnected through trade.

The Trans-Siberian Railway is one of many links in this international trade. It connects Russia with China, and now with Europe as well.

I think back to my journey across Siberia. If I were a young male chimpanzee venturing so far from home, I would have been killed by the first group of foreign males I met.

But traveling deep into what had been enemy territory, I was never threatened. People can benefit from a stranger, if only by having someone to talk with, and share their vodka.

So what can chimpanzees tell us about war?

War is natural, but it is not inevitable.

People, like chimpanzees, are sensitive to both costs and benefits.

We can reduce war by increasing its costs, and by increasing the benefits of peace.

And what gives me hope is that the people I’ve met traveling around the world – they don’t want mutually assured destruction. They want the simple things listed in the Pink Floyd song about in the Post-war Dream:

A place to stay.

Enough to eat.

Somewhere old heroes shuffle safely down the street.

You can relax on both sides of the tracks

And maniacs don’t blow holes in bandsmen by remote control.

And everyone has recourse to the law.

And no one kills the children anymore.