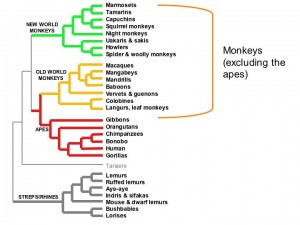

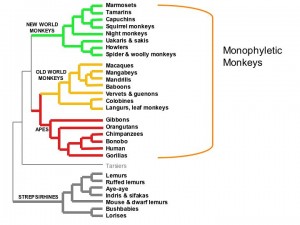

A few minutes after we drove into Lake Itasca State Park, a large animal with glossy black fur crossed the road in front of us. Since we were in Minnesota, not Africa, I had to suppress my first impulse to think it might be a chimpanzee or gorilla, and decided it must be a black bear instead. The bear casually shuffled along, watching us indifferently as it crossed the road. As much as I enjoyed seeing the bear, it it did make me rethink my plans to go running through the park with the baby in the jogging stroller.

Visiting Minnesota’s first state park prompted many comparisons with Gombe National Park in Tanzania, where I have been doing fieldwork for much of the past 10 years.

In the early 19th Century, both parks were part of vast wilderness areas, still largely unexplored by Europeans. In both cases, English-speaking Europeans visited the area searching for the source of great rivers. Henry Schoolcraft determined that Itasca was the source of the Mississippi in 1832. Previous explorers had identified various other lakes as the Mississippi’s source, but Schoolcraft seems to have been the first to ask the locals for directions. Schoolcraft had learned to speak the Ojibwe language from his wife, Jane, and when he asked for directions, he had the good fortune to meet Ozaawindib, who hunted in the area and knew the lakes and rivers perfectly well, and agreed to show Schoolcraft the way.

Not long after, in 1858, Richard Burton became the first European to see Lake Tanganyika, which he claimed to be the source of the Nile. Had he arrived some 10 or 20 million years earlier, in the Miocene, he would have been correct. But since then, the Virunga Volcanoes had risen and blocked the flow to the Nile; now Tanganyika empties into the Congo River instead.

Being identified as the source of the Mississippi proved key to Itasca’s eventual protection as a state park. Gombe lacked such a geographical distinction, but had chimpanzees, which was enough to arouse interest in protecting the area.

While it was interesting to see the official source of the Mississippi (and fun floating down the infant river), the really striking thing about Itasca was the trees.

It’s easy to feel a bit smug about forests in Minnesota. After all, forests still cover much of the state – quite a contrast to central Illinois, where I grew up, where hardly any of the original habitat (tallgrass prairie) remains. What Itasca makes clear, though, is that these forests are, by and large, scrubby remnants. When Europeans first came to Minnesota, the state’s vast pine forests boasted many giant pines, said to reach 200 feet tall.

In 1837, the Ojibwe signed the Treaty of St. Peters, trading millions of acres of land for a promise of government subsidies. Logging companies moved in fast, and within a single man’s lifespan, cut down pretty much all the trees worth cutting.

By the time Jacob Brower visited Itasca in 1888 to settle a surveying dispute, Itasca had one of the few significant patches of old growth pine forest left in the state. Brower lobbied to protect the pines, and as a result in 1891 Minnesota established its first state park at Itasca. So now we can get a glimpse of the forest that used to cover so much of the state: stately red and white pines, hundreds of years old. In a modest, Midwestern sort of way, these forests bring to mind the great Ponderosa Pines of Yosemite Valley – a far cry from the usual thick tangle of aspen, birch, and (compared to Itasca) gawky adolescent pines and spruces that cover so much of Minnesota today.

Minnesota has had some conservation successes. We have a healthy population of top carnivores: 3,000 wolves (the largest population in the lower 48 states), over 20,000 black bears, and occasional visits from cougars. Species that were nearly eliminated from the state, like bald eagles, wild turkeys, and peregrine falcons, have made impressive recoveries. But the great pine forests will take centuries to recover — if they ever do.