Our recent paper on lethal aggression (Wilson et al., 2014) has attracted lots of attention, most of it positive. Not surprisingly, though, some critical responses have also emerged. Copied below is our response to one of these critiques.

John Horgan at Scientific American devoted a blog post to critiquing the paper — though this critique is not really focused on the paper, but on whether the paper’s findings support what Horgan calls the “deep roots theory of war.” Horgan later published a critique by Brian Ferguson, the main advocate of the Human Impacts Hypothesis. In introducing this critique, Horgan offered to post responses from any of the original paper’s authors. We therefore have written a response, which is now posted here. In case it might be useful, I’ve copied it here as well:

Human impacts are neither necessary nor sufficient to explain chimpanzee violence (or bonobo non-violence)

Michael L. Wilson, Christopher Boesch, Takeshi Furuichi, Ian C. Gilby, Chie Hashimoto, Catherine Hobaiter, Gottfried Hohmann, Kathelijne Koops, Tetsuro Matsuzawa, John C. Mitani, David Morgan, Martin N. Muller, Roger Mundry, Anne E. Pusey, Julia Riedel, Crickette Sanz, Anne M. Schel, Michel Waller, David P. Watts, Frances White, Roman M. Wittig, and Richard W. Wrangham[1]

In response to our recent paper (Wilson et al., 2014), Brian Ferguson (2014) critiques the methods we used to test whether chimpanzee violence is the result of human impacts. As Joan Silk notes in her commentary on our paper, “These results should finally put an end to the idea that lethal aggression in chimpanzees is a non-adaptive by-product of anthropogenic influences — but they will probably not be enough to convince everyone” (Silk, 2014: 321).

We expect that for the majority of primatologists, and among the wider community of animal behavior researchers, the results of our study are neither surprising nor controversial. But for those hostile to the idea that human violence relates in any way to biology or adaptive behavior, the Human Impacts Hypothesis (HIH) offers an out. Violence among our ape cousins is, in this view, the result of human contact, not the result of evolution favoring aggression as a strategy. The argument closely parallels Ferguson’s earlier argument that violence in tribal societies is mainly the result of contact with outsiders, especially European imperialists (Ferguson, 1990).

In contrast to some critics, Ferguson recognizes that “there is no question that chimpanzees have the capability to make war and have done so on occasion” (Ferguson, 2011: 249). Ferguson’s critiques thus represent a departure from what we might call the “strong anti-adaptationism” of previous proponents of the HIH. For example, Power (1991) argues that chimpanzee violence is a non-adaptive response to frustration caused by restrictive feeding methods at the first long-term study sites of chimpanzees, Gombe and Mahale. Ferguson embraces Power’s hypothesis that feeding chimpanzees made them more violent, but in contrast to Power, he argues that chimpanzee violence is mainly the result of resource competition, which is exacerbated by human activities such as feeding and deforestation. This argument differs little from arguments that behavioral ecologists regularly make to explain chimpanzee violence. For example, intercommunity violence in chimpanzees is strongly associated with competition over food resources. At Kanyawara, intercommunity encounters occurred most frequently when key food species were abundant in areas bordering neighboring communities (Wilson et al., 2012). Lethal aggression is strongly associated with territorial expansion at Ngogo (Mitani et al., 2010) and Gombe (Goodall, 1986), and by expanding territory chimpanzees increase the amount of food available to themselves, their mates and offspring (Williams et al., 2004; Pusey et al., 2005).

However, in his critique, Ferguson seems to conflate “resource competition” with “disturbance brought about by the actions of people.” Resource competition is not necessarily a “disturbance”, nor does it occur only as a consequence of “disturbance.” Instead, resource competition is a routine part of existence for living things. This is one of the central premises of evolution by natural selection, and evolutionary disciplines such as behavioral ecology. Ferguson therefore appears to agree with us that violence is an adaptive strategy for resource competition. And we agree that actions of people can sometimes affect resource competition in other animals, for example by adding a valuable, concentrated resource (Wrangham, 1974), or by removing key resources such as fruit trees, increasing competition for available land (Goodall, 1977). What we disagree on is whether the evidence indicates that human impacts are the main cause of chimpanzee violence.

Ferguson argues that “human impact must be approached in historical detail.” The 30 co-authors of our paper are deeply familiar with the historical details, with many of them having been involved in these long-term sites for decades. But historical awareness does not preclude a scientific approach. Clear predictions emerge from the hypothesis that human impacts cause chimpanzees to kill. We have sought to test those predictions systematically. We also appreciate that our study sites and study populations, and the human populations that now surround those sites, have complex histories that long pre-date our research projects, and that we should be aware of this fact despite the difficulties of reconstructing these histories. However, we are also concerned with history in another sense: the evolutionary history of chimpanzees. For the great majority of this history, chimpanzees and their immediate ancestors could not have been subject to “disturbance” of the kinds that Ferguson and other proponents of the HIH invoke.

When introducing Ferguson’s critique, John Horgan writes of confirmation bias, which is indeed a concern in any scientific endeavor. To counter this bias, scientists use tools such as collecting quantitative data and using statistical methods to test which models best explain the observed data. In our study, we sought to use methods that are objective and transparent, and which would provide well-substantiated answers, whether they agreed with our prior opinions or not.

In contrast, the “holistic” approach promoted by Ferguson is vulnerable to confirmation bias. Without clearly defining variables such as disturbance, and without using quantitative data and statistical methods designed to test whether a given set of results is likely given the available sample size, efforts to compare contrasting interpretations of a given set of data risk degenerating into cherry picking and special pleading.

Ferguson argues that “[t]he three measures Wilson et al. created to test for human impact are questionable.” However, he agrees in principle with each of these measures, and offers no quantifiable alternatives.

He states that our first measure, “artificial provisioning of food, is good, where it applies, though the impact of provisioning varies by how it is carried out and other conditions of food availability.” By this Ferguson presumably refers to the argument of Power (1991) that the “restricted” provisioning at Gombe and Mahale is what frustrated chimpanzees and (in Power’s view) fundamentally changed their behavior.

We do not dispute that providing food can change the behavior of chimpanzees and other animals. Wrangham (1974) found that at Gombe, chimpanzees and baboons were more aggressive in the feeding area than when foraging for natural foods away from the feeding area. What is clear from our study, however, is that provisioning is neither necessary nor sufficient for chimpanzees to kill.

We examined data on both chimpanzees (18 communities at 10 study sites) and bonobos (4 communities at 3 study sites). Of these sites, provisioning occurred at two chimpanzee sites (Gombe and Mahale) and one bonobo site (Wamba).

Evidence for lethal aggression has been found in seven of the of eight never-provisioned study sites (Budongo, Fongoli, Goualougo, Kalinzu, Kibale, Kyambura, Taï); the only exception is the small, isolated population at Bossou. Ferguson notes that “sites marked P for provisioning cluster (4 out of 7 cases) toward the high end of the killing distribution.” Fair enough, but the two highest rates of killing are for sites where chimpanzees were never provisioned. Moreover, at Mahale and Gombe, killings have continued to be observed long after provisioning ended (in 1987 and 2000, respectively). Killings by never-provisioned chimpanzees have also been reported at shorter-term study sites not included in our study, including Loango in Gabon (Boesch et al., 2007), as well as Conkouati-Douli National Park, Congo, where male wild-born, captive chimpanzees released into the wild were attacked by resident chimpanzees (Goossens et al., 2005).

Ferguson claims that “Provisioning’s statistical association with killing, however, is diluted by two other sites,” Mahale’s K-group and Wamba. “Diluted” is an odd choice of words here; if provisioning causes chimpanzees to become violent, then presumably every community provides relevant data, rather than dilution. Excluding K-group from the analysis would involve picking and choosing, excluding any data that doesn’t fit the expectation (in other words, guaranteeing confirmation bias).

Provisioning is thus clearly not necessary for chimpanzees to kill. Nor is it sufficient for killing to occur. Killings have been observed at both of the historically provisioned chimpanzee sites, but the observed and inferred killings by the Mitumba community at Gombe occurred only after provisioning ended there (Wilson et al., 2004). (We note, though, that one infanticide is suspected to have occurred at Mitumba during the time that Mitumba chimpanzees were provisioned (Pusey et al., 2008)).

Killings have not been observed at the provisioned bonobo site (Wamba). The one suspected bonobo killing took place at a non-provisioned site (Lomako). Ferguson notes that bonobos are a different species. Of course, this is true. But if provisioning causes chimpanzees to kill, why should it not cause other species to kill, especially closely related species?

Ferguson argues that Wamba should not be included in the analysis because bonobos are a different species. Fair enough; and indeed, in Table 3, we present results focused on just chimpanzees, excluding bonobos, and found that provisioning history did not explain variation in rates of killing among chimpanzee communities. But we also note that Ferguson has previously written that violence in chimpanzees is the result of social learning, proposing that bonobos would behave like chimpanzees if they experienced similar conditions (“What would happen if a bonobo were raised among chimpanzees or vice versa? I expect their behaviors would reflect the local custom” (Ferguson 2011: 255)). Following this line of logic seems to suggest to us that exposing bonobos to the same stimulus as chimpanzees (provisioned food) should result in a similar increase in aggressive behavior. But the one suspected case of killing by bonobos occurred at the never-provisioned site of Lomako, rather than the provisioned site of Wamba.

In our view, the much less frequent occurrence of violent aggression in bonobos compared to chimpanzees raises interesting questions about the evolution of non-violence as well as violence.

We note with interest, though, that Ferguson’s argument for provisioning is profoundly different from Power’s argument. Power argued that restricted provisioning fundamentally changed the behavior of chimpanzees at Gombe and Mahale, and that a wide range of chimpanzee behaviors reported by researchers there were the result of provisioning: male dominance hierarchies, despotic alpha males, possessive sexual behavior, closed membership of social groups, territorial behavior, female dispersal, hunting of monkeys, and intergroup killings. Studies of never-provisioned chimpanzees have found that all of these behaviors occur in the absence of provisioning. We can therefore reject the idea that chimpanzee behavior is fundamentally altered by provisioning. And indeed, instead of following Power’s argument that chimpanzee violence is maladaptive, Ferguson accepts that chimpanzee violence is an adaptive component of resource competition.

As a second measure of human impacts, we examined size of protected area. Ferguson notes that “some chimpanzee groups living within large protected areas have been heavily impacted.” Fair enough. That is why we conducted multivariate analyses considering several different variables. However, size of protected area is a measure that is readily quantified, and is likely important both for chimpanzee conservation and as a general measure of the degree to which chimpanzees have been affected by human activities. Like our other measures of human disturbance, however, size of the protected area did not have a consistent effect on rates of violence.

Our third measure of human impacts was an index of disturbance, based on a method developed by Naomi Bishop and colleagues for assessing the impacts of human activities on Hanuman langur monkeys in India (Bishop et al., 1981). Ferguson agrees that these measures “work well as a general index of over-all human impact,” but complains that “they do not work as predictors of intensified violence.” Similar complaints could be made of any effort to quantify human disturbance, because what exactly qualifies as disturbance is never clearly stated. However, it is worth pointing out that the disturbance index developed we used was originally developed to address a controversy over causes of infanticide (Bishop et al., 1981).

Importantly, for our disturbance rankings, each site director ranked their own site without prior knowledge of the rankings of other researchers. These rankings thus provide an independent estimate of disturbance made by the people who best know each of these sites.

Ferguson notes that Budongo has been exposed to various forms of lumber extraction, and other chimpanzee sites have experienced “islandization.” Fair enough. As primatologists actively involved in conservation efforts, we are deeply familiar with such issues at our sites. Capturing all of these different effects in a single variable, or a single index that combines several measures of disturbance (the approach we used), can never be wholly satisfactory. But we believe that the rankings that we did for our study do correlate reasonably well with the degree to which these different sites have been affected by humans. Goualougo is clearly the least affected chimpanzee site, and Bossou the most. Kanyawara, at the edge of Kibale National Park, has a higher disturbance rating than Ngogo, at the center of the park. We do not argue that our index is perfect, but we are not aware of a better one.

Ferguson points to many different possible impacts: provisioning, habitat clearance, timber extraction, hunting, and so on. Some of these could well have an effect on chimpanzee violence, by (for example) increasing the intensity of competition for resources. This is an adaptationist argument following standard theory in behavioral ecology, and as such, is an approach that we find reasonable. It is the fact that these are reasonable questions that motivated us to conduct our study. Given the possibility that human activities can affect rates of violence in chimpanzees, it is important to investigate the extent to which the observed patterns of violence reflect human impacts. This is what we have attempted to do, using data that are quantifiable, systematic, defined using the same criteria across study sites, and using a statistical approach that allows us to test predictions from multiple contrasting models. We found that human impacts did not explain the variation in rates of lethal aggression as well as other factors. Eastern chimpanzees killed more often than western chimpanzees, which killed more often than bonobos. Communities with more males and communities living in denser populations killed more frequently than communities with fewer males and sparser populations.

It is not at all clear why chimpanzees should react this way when exposed to humans, but not bonobos, baboons, or other species. For example, baboons have been studied at Gombe almost as long as chimpanzees and have been influenced by human activity. But they have not been observed to participate in coalitionary killing. What accounts for such differences between species when exposed to precisely the same human impacts? The absence of coalitionary killing in baboons makes sense from an evolutionary perspective (Wrangham, 1999), but is inexplicable from an anti-adaptationist perspective.

Moreover, chimpanzees and humans are far from the only species to engage in lethal aggression. Fatal fighting occurs widely among animals, and includes a broad range of examples, such as fatal fights among male spiders competing for mating opportunities (Leimar et al., 1991) and the killing and consumption of male spiders by female spiders, after (or sometimes during or even before) the males have mated (e.g., Andrade, 1996). Most such fatal fighting involves fights between individuals over a highly valuable resource. In contrast, coalitionary killing occurs in fewer species, and seems mainly limited to certain social insects, social carnivores such as wolves, lions and spotted hyenas, and a few primates, including humans and chimpanzees (Wrangham, 1999). Why coalitionary killing occurs in these species but not others is explicable, in principle, using the comparative method to develop testable hypotheses. An anti-adaptationist approach promises no such explanatory power.

Whether chimpanzee violence is adaptive or not, is a question for which we do not yet have a definitive answer. Answering this question in full requires information on reproduction and information on individual participation in violence, which is available for only a few sites and which has not yet been analyzed. Additionally, chimpanzees (like humans and other animals) may sometimes make mistakes, participating in killings that result in fitness (i.e. reproductive) costs. Whether a given behavioral strategy is adaptive depends on average effects of traits. Given these caveats, previous studies provide evidence in support of the view that chimpanzee violence provides fitness benefits to the attackers. Mitani et al. (2010) found that the intergroup killings by the Ngogo community were associated with substantial territorial expansion in the area where disproportionately many of the killings had taken place. Studies at Gombe provide evidence that larger territories provide important fitness benefits, including more food, as indicated by heavier individual body weights, controlling for age and reproductive condition (Pusey et al., 2005) and shorter inter-birth intervals for females (Williams et al., 2004). Males who enlarge their territory thus provide more food for their mates and offspring, enabling faster reproduction, and thus greater reproductive success for the aggressors.

In his critique, Ferguson mostly ignores the second focus of our paper: the pattern of attackers and victims. We found that most participants (92%) were male, as were most victims (73%). Most victims were members of other communities (63%). Intercommunity killings generally involved gang attacks, in which attackers outnumbered victims by a factor of 8:1. These patterns make sense when seen as adaptive strategies. Male chimpanzees defend group territories; eliminating members of rival communities enables males to increase the amount of food available to themselves, their mates, and offspring (Williams et al, 2004; Pusey et al., 2005; Mitani et al., 2010). Chimpanzees prefer to attack when the odds are in their favor (Wrangham 1999; Wilson et al., 2012). Viewing these behaviors solely as a non-adaptive response to human disturbance provides no insights into why attacks mainly involve males attacking members of other groups when the odds are in their favor.

The question of what, if anything, chimpanzee violence has to do with human warfare is one we did not address in our paper. We expect that among our 30 co-authors some diversity of opinion exists on this topic. We would all agree, though, that definitive claims about human behavior need to be based on data from humans.

Nonetheless, there are some important things we can learn from chimpanzee studies. Our study examines lethal aggression broadly, including infanticide and within-community violence. Despite this, the criticisms of Ferguson (as well as John Horgan’s earlier post) focus mainly on intercommunity killing, and its relevance to studies of human warfare. Ferguson, Horgan, and many others argue that warfare has a relatively recent origin (within the past 10,000 years (Ferguson, 2003)), due to some relatively new phenomenon, such as agriculture, or settled societies, or food storage, or property rights, or ideology, or new kinds of weapons. Chimpanzees have none of these things. They do sometimes use weapons (sticks and stones) but they don’t generally use them to kill each other. So the documentation of warlike behavior in chimpanzees shows that similar behavior could have occurred in humans long before the origin of agriculture and other evolutionarily recent innovations. It also raises the intriguing possibility that humans and chimpanzees share similar patterns of violence due to our shared evolutionary history; we may have inherited these patterns of behavior from our common ancestor.

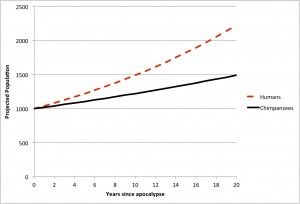

As many have noted, however, and as we fully recognize, the existence of bonobos, with their much less violent societies, highlights the need to be cautious in how much we infer along these lines. It is possible that the lineages leading to humans and chimpanzees have both become more violent, or that the lineage leading to bonobos has become more peaceful over evolutionary time. We don’t yet know the answer to this question.

We heartily agree with Silk’s point that “Humans are not destined to be warlike because chimpanzees sometimes kill their neighbours” (Silk, 2014: 322). Variation in rates of warfare among countries today, and across historical time, clearly show that people can develop institutions and mechanisms that reduce the frequency and severity of warfare (Gat, 2006; Pinker, 2011). Chimpanzee communities also vary considerably in their rates of intercommunity violence. As we have found, this variation is better explained by differences among species, populations, and demography than by human impacts (Wilson et al., 2014).

References

Andrade, M. C. B. (1996). “Sexual selection for male sacrifice in the Australian redback spider.” Science 271(5245): 70-72.

Bishop, N., S. B. Hrdy, J. Teas and J. Moore (1981). “Measures of human influence in habitats of South Asian monkeys.” International Journal of Primatology 2(2): 153-167.

Boesch, C., J. Head, N. Tagg, M. Arandjelovic, L. Vigilant and M. M. Robbins (2007). “Fatal chimpanzee attack in Loango National Park, Gabon.” International Journal of Primatology 28: 1025-1034.

Ferguson, R. B. (1990). “Blood of the Leviathan: Western contact and warfare in Amazonia.” American Ethnologist 17(2): 237-257.

Ferguson, R. B. (2003). “The birth of war.” Natural History 112(6): 28-35.

Ferguson, R. B. (2011). Born to Live: Challenging Killer Myths. Origins of Altruism and Cooperation. R. W. Sussman and C. R. Cloninger: 249-270.

Ferguson, R. B. (2014). “Anthropologist Brian Ferguson challenges claim that chimp violence is adaptive.” Retrieved 19 September 2014, from http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/cross-check/2014/09/18/anthropologist-brian-ferguson-challenges-claim-that-chimp-violence-is-adaptive/.

Gat, A. (2006). War in Human Civilization. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Goodall, J. (1977). “Infant killing and cannibalism in free-living chimpanzees.” Folia Primatol 22: 259-282.

Goodall, J. (1986). The Chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of Behavior. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Belknap Press.

Goossens, B., J. M. Setchell, E. Tchidongo, E. Dilambaka, C. Vidal, M. Ancrenaz and A. Jamart (2005). “Survival, interactions with wild conspecifics and reproduction in wild-born orphan chimpanzees following release into Conkouati-Douli National Park, Republic of Congo.” Biological Conservation 123: 461-475.

Leimar, O., S. Austad and M. Enquist (1991). “A test of the sequential assessment game: fighting in the bowl and doily spider Frontinella pyramitela.” Evolution 45(4): 862-874.

Mitani, J. C., D. P. Watts and S. J. Amsler (2010). “Lethal intergroup aggression leads to territorial expansion in wild chimpanzees.” Current Biology 20(12): R507-R508.

Pinker, S. (2011). The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined, Viking.

Power, M. (1991). The Egalitarians—Human and Chimpanzee: An Anthropological View of Social Organization. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Pusey, A. E., G. W. Oehlert, J. M. Williams and J. Goodall (2005). “The influence of ecological and social factors on body mass of wild chimpanzees.” International Journal of Primatology 26: 3-31.

Pusey, A. E., C. Murray, W. R. Wallauer, M. L. Wilson, E. Wroblewski and J. Goodall (2008). “Severe aggression among female chimpanzees at Gombe National Park, Tanzania.” International Journal of Primatology 29(4): 949-973. get pdf

Silk, J. B. (2014). “Animal behaviour: The evolutionary roots of lethal conflict.” Nature 513(7518): 321-322.

Williams, J. M., G. Oehlert, J. Carlis and A. E. Pusey (2004). “Why do male chimpanzees defend a group range? Reassessing male territoriality.” Animal Behaviour 68(3): 523-532.

Wilson, M. L. (2012). Long-term studies of the Gombe chimpanzees. Long-term Field Studies of Primates. P. Kappeler and D. P. Watts. Heidelberg, Springer-Verlag: 357-384. get pdf

Wilson, M. L., C. Boesch, B. Fruth, T. Furuichi, I. C. Gilby, C. Hashimoto, C. Hobaiter, G. Hohman, N. Itoh, K. Koops, J. Lloyd, T. Matsuzawa, J. C. Mitani, D. C. Mjungu, D. Morgan, R. Mundry, M. N. Muller, M. Nakamura, J. D. Pruetz, A. E. Pusey, J. Riedel, C. Sanz, A. M. Schel, N. Simmons, M. Waller, D. P. Watts, F. J. White, R. M. Wittig, K. Zuberbühler and R. W. Wrangham (2014). “Lethal aggression in Pan is better explained by adaptive strategies than human impacts.” Nature 513: 414-417.

Wilson, M. L., S. M. Kahlenberg, M. T. Wells and R. W. Wrangham (2012). “Ecological and social factors affect the occurrence and outcomes of intergroup encounters in chimpanzees.” Animal Behaviour 83(1): 277-291. get pdf

Wilson, M. L., W. Wallauer and A. E. Pusey (2004). “New cases of intergroup violence among chimpanzees in Gombe National Park, Tanzania.” International Journal of Primatology 25(3): 523-549. get pdf

Wrangham, R. (1974). “Artificial feeding of chimpanzees and baboons in their natural habitat.” Animal Behaviour 22: 83-93.

Wrangham, R. W. (1999). “The evolution of coalitionary killing.” Yearbook of Physical Anthropology 42: 1-30.

[1] We invited all co-authors of our original paper to contribute to this response. All of those who responded to our invitation provided feedback and asked to be included as co-authors. Most (or perhaps all) of those who have not yet responded to this request are currently in the field with limited access to email. Not being included on this list, therefore, does not necessarily imply any disagreement with the contents of this response.